BY COLLEEN KEANE

SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

ALBUQUERQUE — On Easter Sunday, Loreal Tsingine, a 27-year old Diné woman who stood about 5 feet tall, was shot five times by Austin Shipley, a police officer of Winslow, Arizona. She died alone on the city street, leaving behind her teenage daughter, family, and friends.

Winslow police say that Tsingine resisted arrest and was brandishing a pair of scissors at the time she was surrounded by Shipley and another armed officer, who, from photographs, appeared to be twice her size.

No criminal charges were brought against Shipley by the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, according to reports.

Seeking justice one stormy day last July, family and friends, along with members of the Red Nation, a Native rights advocacy group, marched on the Winslow Police Department.

But, once there, Red Nation co-founder Melanie Yazzie, a scholar and an activist, said that justice was nowhere in sight.

In its place was a physical barrier. As Tsingine’s loved ones faced the barrier, a thunderstorm broke out.

To Shiprock Chapter President Chili Yazzie, who stood by Tsingine’s family that day, it was a spiritual sign that Tsingine knew they were there and appreciated their presence.

And at that moment, the marchers, mostly women and children, broke through the barrier and marched on to the police department.

“We kicked over the barricades. It was time for the warrior side of the Diné to come out. We have to fight to get out justice,” recounted Melanie Yazzie.

Yazzie recounted how the community resisted the Winslow police department on July 29 during a forum at the University of New Mexico on Oct. 11 celebrating the 2nd Indigenous Peoples’ Day of Resistance and Resilience.

The forum, called Re-articulations of Native Savagery, was hosted by the Institute for American Indian Research, the Kiva Club, and the Department of American Studies.

The morning session included the talk by Melanie Yazzie (Diné), along with presentations by activist and filmmaker Norman Patrick Brown (Diné), a member of the American Indian Movement in the1970s; Jennifer Marley, (San Ildefonso), Kiva Club vice president; and Lazarus Nance Letcher, a Ph.D. student exploring coordinated resistance between African-American and Native American communities.

About 100 students, mostly Native American, attended the forum, which took place in Zimmerman Library.

Continuing her description of what happened that July day in Winslow, Yazzie said, “We were feeling intense grief. So, we left (our grief) where it belongs — in the hands of the perpetrators who had barricaded us. These were powerful moments of people-based justice.”

She noted that soon after, the U.S. Department of Justice agreed to finally step up and investigate Tsingine’s death.

Yazzie stressed that it’s important to acknowledge community-based victories like this one, because they provide counter-narratives to mainstream interpretations of Native history.

Giving an example, she referred to a story by Chicago-based journalist Kelly Hayes, who described the recent shutdown of the North Dakota pipeline as an illusion of victory for Native American communities, referring to it as a ploy by the federal government to look like it was doing something.

“Hayes gets it wrong on how tribal citizens understand victories,” Yazzie told the group.

“We don’t have to concentrate on the state or federal government. Native people know what colonialism is. We don’t need an education on that. Rather, we should concentrate on what we’re doing,” she stressed.

“Thousands of our relatives are being attacked for protecting the land and water from the black snake. Our people are putting their lives on the line. We refuse to back down even when the costs are high. This is the spirit at Standing Rock,” she said.

It is the same spirit, she said, that mobilized Natives to break through the police barrier in Winslow, abolish Columbus Day and establish Indigenous Peoples Day, to nearly abolish the UNM seal that depicts a frontiersman and a conquistador, and raise their voices against the celebration of the Entrada, the entrance of the Spanish into New Mexico, to name a few.

“These are Native victories. They are from our refusal to stop resisting. They don’t belong to the government,” she said.

Recalling, in part, the history of Native resistance, panelist Brown recalled how he traveled with 35 Diné elders to Washington, D.C. in the 1970s to protest the relocation of Diné families during the Navajo/Hopi Land Dispute.

“The spirit or resistance was born when we returned to our camp at Big Mountain,” he said.

Brown, now 56, attributed the strength of the movement to Diné mothers and grandmothers.

“It was the women who had a major say on how this resistance was created. I see it today,” he said.

One of the women Brown refers to is Marley.

As a panelist, Marley brought attention to the mainstream narrative that erased Pueblo history.

“The only part that’s usually mentioned in New Mexico history books is the Pueblo Revolt of 1680,” she said adding that this version doesn’t reflect what really happened.

“The rebellion wasn’t spontaneous. That’s a myth. It took at least five years of planning with the participation of entire Pueblo communities. Pueblo people knew a fullblown revolution was needed,” she said.

She also noted that when the Spanish returned 12 years after the Pueblo Revolt, it wasn’t a peaceful situation as reflected in New Mexico history books.

“There was nothing peaceful about the second coming. There was violence. Pueblo communities resisted,” she said.

She explained that during the years that followed, Spanish descendants secured massive land grants from the indigenous land base.

“They were the new class of citizens, the Spanish-Americans,” she said.

At the same time, tribal members, who were denied property rights, endured indentured labor in order to survive and were given Spanish surnames — stripping them of their tribal identity.

“Pueblo people were exploited as a people without history and of little status,” she said.

Today, she said that border towns with their high rates of homelessness, poverty, suicide, and violence continue the colonial process, as do gentrified cities like Santa Fe, which has evolved into a hub for the wealthy Anglo population.

“Santa Fe allows this romantic idea of Native culture to flourish, so it can be sold for profit,” she said.

Marley said that challenging the mainstream narrative is one way to resist colonialism. Another is celebrating the strength of Native people and culture, she advised.

“In the spirit of (Pueblo Revolt leader) Po’pay, we need to move forward,” she said.

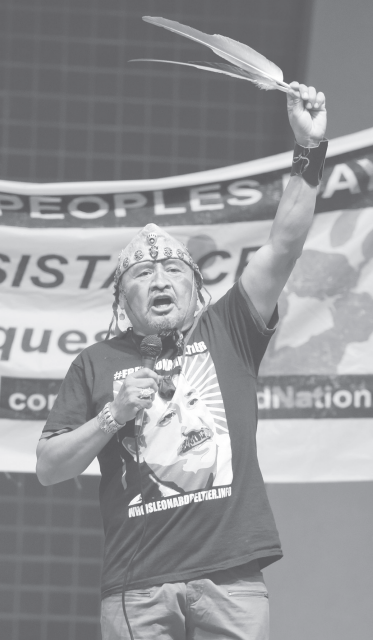

NAVAJO TIMES | DONOVAN QUINTERO

Norman Brown holds a pair of feathers over his head on Oct. 10 during Indigenous Peoples Day in Albuquerque.