BY COLLEEN KEANE

SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

ALBUQUERQUE — Jaaʼabaní, bat, has always been a helper to the Diné and all people of the earth.

They are selfless beings, notes the “Legends and Culture” section on Twin Rocks Trading Post’s website.

“Bats were part of the council called upon to mediate after the war between the Dark Thunder People and the Winter Thunder group. As a representative of the “great gods,” bat, who occupied the humblest seat near the door, consented to go and (renew) peace to both Thunder groups,” the description reads.

Besides building bridges in the spirit world, Diné cosmology attributes jaaʼabaní with silently passing along answers to difficult questions when humans are put on the spot and quietly helping out the Holy People when they need backup.

In everyday life, Jaaʼabaní keeps the earth in balance by pollinating flowers and plants, and guards against invasive insects that destroy crops and farm lands.

Now, jaaʼabaní is in trouble and needs the help of humans to survive.

While jaaʼabaní has several predators, like cats, owls and hawks, a microscopic fungal spore has become the biggest threat of all.

The spore, pseudogymnoascus destructans or Pd for short, sneaks up on jaaʼabanís when they’re hibernating in cold, dark places, like caves. Called White Nose Syndrome because the microscopic spores attach to the jaaʼabanís’ noses and ears, the fungus sucks the life out of the small mammals as they sleep hanging upside down.

“While hibernating, bats have a certain amount of fat that lasts them until spring when the insects return and the temperature warns up,” said biologist Justin Stevenson. “If (that gets used up) and they get dehydrated, they die.”

Stevenson was one of several wildlife specialists who presented information about the delicate nature of the bat ecosystem during last weekend’s Bird and Bat Festival held at the Rio Grande Nature Center on the northwest side of the city.

He said that since 2006, more than six million bats in the U.S. and Canada have died from Pd.

Researchers first discovered the noxious spore on a routine count of the New England bat population.

“They sadly saw dead bats in the snow, dead bats carpeting the cave,” explained Stevenson.

Pd was introduced into the United States by a European tourist who carried it into an east coast cave on his or her hiking boots.

It quickly spread from one cave to another.

According to one source, WNS has killed big brown bats, tri-colored bats, little brown bats, eastern small-footed bats, northern bats and Indiana myotis bats.

“It’s very tragic and incredibly devastating,” said Stevenson.

While Pd hasn’t reached the southwest, Stevenson said there’s concern that it will.

“A lot of biologists have hoped that the west would not have a problem because (the environment) is hot and dry. But, researchers from UNM and other (academic institutions) conducted extensive studies and found that under the right conditions, Pd could grow and populate,” he explained.

He added that unlike the bat cave systems back east, bats here in the Southwest live in varied environments that include caves, crevices, rock formations, deserted barns and other dwellings, which aren’t as easy to monitor.

“We don’t have great ability to count our bats throughout the west,” he noted. “If we can’t see them, can’t fi nd them, it’s a big uphill battle to know if Pd is here and how it’s effecting our bats.”

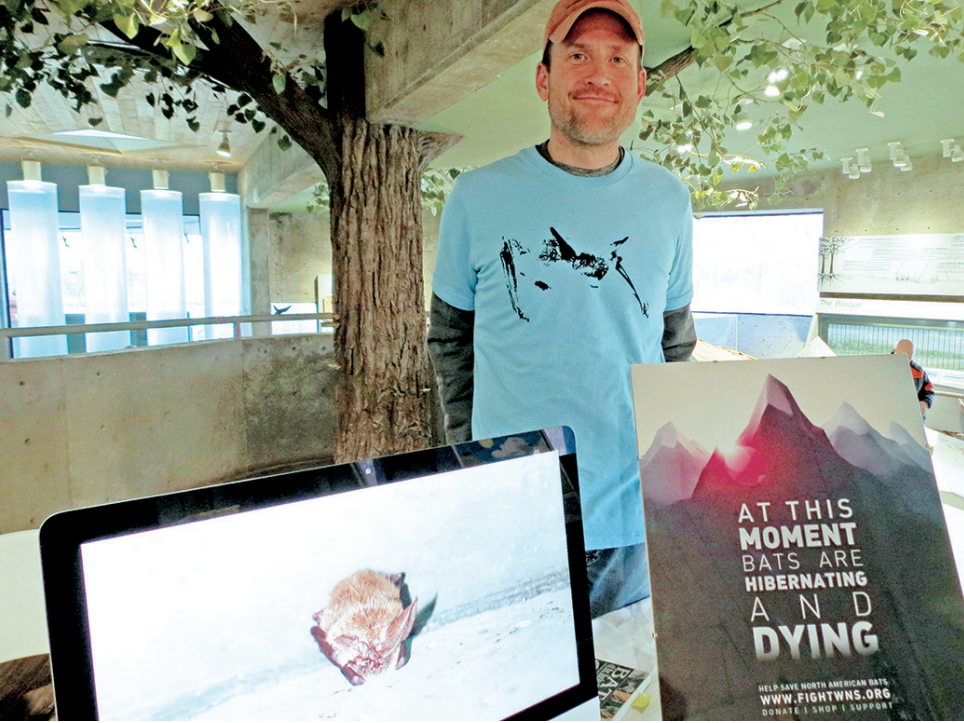

Stevenson along with his wife, Holly Smith, also a New Mexico wildlife biologist, founded Fight WNS, a non-profit organization that’s funding research.

SPECIAL TO THE TIMES | COLLEEN KEANE

New Mexico wildlife biologist Justin Stevenson educates people on a fungus that’s killing millions of bats when they hibernate.