COURTESY | SEACOURT PRINT CENTER

Close up of Schwemberger’s photo of nine Diné girls, with Eleanor Chee in the middle and others openly ex-pressing their contempt for the activity.

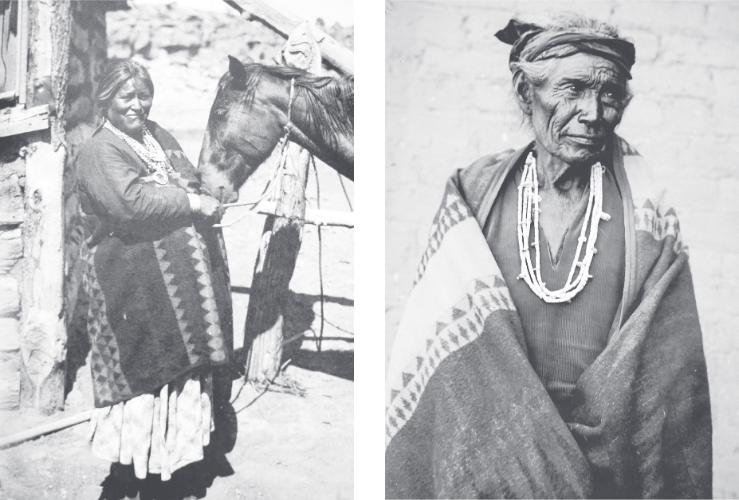

Schwemberger’s photo of “Mrs. Whitegoat” is one of hundreds that he took shedding light on life for Diné families at the turn of the 20th century.

This image taken in the 1900s by George Charles Schwemberger, known as “Big Eyes” to the Diné, is identified as “Dine Tsosi, the last of the Navajo war chiefs.”

BY COLLEEN KEANE

SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece ran in last week’s paper without the photographs to which the author refers. Since the photographs are the focal point of the story, we’re running it again, with the photographs this time.

ALBUQUERQUE/BELFAST, Northern Ireland — With a blanket shrouding his shoulders, a bandana tied around his forehead, the image of a Navajo elder from the 1900s grabs my attention.

The caption reads, “Dine Tsosi, the last of the Navajo war chiefs.”

It appears to have been penned at the time by the photographer, Brother Simeon, a Franciscan Fryer who was stationed at St. Michaels Mission in Arizona, from 1902 to 1908.

Simeon, his clerical name, was born George Charles Schwemberger.

To the Diné, he was known as Anaa’tsoh, Big Eyes.

At the start of the 20th century, when photographic equipment was just being rolled out, Brother Simeon took it up as a hobby.

It was also a time of harsh transition for tribal families.

I’m mesmerized by the book that features Tsosi, not only because of the haunting look in his eyes, as if he’s removed himself to another place and time, but also because the book bearing the crisp black and white photo is sitting on a bookshelf at the Culturlann McAdam O’Fiaich, an Irish cultural center.

Thousands of miles away from Albuquerque, New Mex- ico, where I freelance report for the Navajo Times, the Culturlann was about the last place I expected to find a book of photographs on Diné history from the early 1900s.

The Culturlann is located on Falls Road west of Belfast’s city center. I was there learning about the history of my father, a native of Ireland’s west coast.

Once a Presbyterian Church, today the building houses the Irish bookstore, a café that specializes in Irish food, art spaces, and classrooms where Gaelic, the Irish language, is taught.

As I hear people in the back- ground softly speaking in my father’s first language, selected photos from the Schwemberger collection take me back to the southwestern United States more than 100 years ago.

In one, a class of Diné children attending St. Michael’s school, their backs to the camera, stare at the figure in the front of the classroom, a Catholic nun wearing her stark black and white habit as she sits behind a desk.

In another, nine Diné girls, who look around 7 years old, their arms raised above their heads, appear to be practicing for a dance performance.

They’re wearing identical dresses all with waistbands and puffy skirts that might have been found in a Sears cata- logue at the time. Large, white ribbons flop out behind their braided hair.

The caption identifies the girl in the middle as Eleanor Chee.

Eleanor has a half-smile on her face, as if someone has prodded her to appear happy, while other girls openly express their displeasure with the ac- tivity in scowls, biting their lips in desperate looks of, “I hope this is over soon!”

On a following page, Mrs. Whitegoat, wearing several strands of beads, a shawl and a long skirt seems to be posing for Schwemberger, as she holds a rope tied around her horse’s neck.

On the opposite page, a young Albert (Chic) Sandoval appears in a three-button-down jacket, vest, white shirt and bow tie, a grim look on his face.

Reading the prologue, I learn that the book is the product of Irish printmakers who answered a call to reproduce selected electronic scans of Schwemberger’s work.

The 16×20 prints were ex- hibited in September 2007 at the Ards Arts Centre in New- townards, Northern Ireland.

Then they toured in museums across Ireland and Britain, stopping apparently for a showing at the Culturlann where the exhibit book caught my eye.

“This collection reveals how static records of past lives can speak to us today,” wrote Robert Peters, the director of the Irish Seacourt Print Workshop that produced the photo catalogue.

But then I wondered, How did Schwemberger’s electronic scans get to Northern Ireland in the first place?

Like the Culturlann, which demonstrates support for international art, the Ards Arts Centre has the same focus.

One of its international partners is sister city Peoria, Arizona.

There in 2005, Peters met Rob Taylor, then chair of the Inter- disciplinary Arts and Performance Center at Arizona State University in Tempe.

It was Taylor who discovered Schwemberger’s glass plate negatives at St. Michaels Catholic Mission in the 1990s.

But by the time Taylor found them, some of the negatives were in different stages of decay after being held in storage for decades by the Franciscans.

In 2005, the mission decided to gift the collection to ASU for safekeeping.

Taylor and his colleagues spent the next years preserv- ing, scanning, digitizing, and archiving the negatives that number more than 1,750.

He then took selected images overseas for international expo- sure and the Seacourt exhibi- tion surfaced.

When I returned to Albuquerque a few weeks after my trip to Ireland, I searched for Taylor and a faculty associate, photo historian Aleta Ringlero, Salt River Pima, to learn more about the exhibit and why it’s significant today.

Calling ASU, I was told Taylor had retired several years ago and provided a referral phone number, but there too the response was that he was no longer at that number.

I turned my attention to contacting Ringlero.

Dialing a possible number in Arizona, I was pleasantly surprised when she answered the phone.

She was delighted that the Navajo Times held interest in the story of the Schwemberger collection.

“These are treasure troves. Here, we have an incredible visual record to know about tribal heritage in a broader picture,” she said.

Continuing, she explained that it’s the details in the imag- es that count the most.

“We’re used to looking at the center image. You have to look at every corner of a photograph,” she advised.

She said that by seeing the less noticeable images, as well as the more obvious scenes, clues emerge on what parents were going through at the time and the reasoning behind their decisions.

She credited Schwemberger, if he realized it or not, for cap- turing the moments when those decisions were in the making.

“The government was forcing parents to make life and death decisions. This isn’t readily recorded except in Schwemberger’s photos,” she said.

Giving an example, she noted that parents who wanted their children to go to school at St. Michaels, close to their homes in Window Rock, Arizona, rather than an agency school far away, were refused food rations by the federal govern- ment.

She added that from carefully studying the photos, we can also get a better understand- ing on how the Diné and other tribal members survived and prospered through it all.

“There’s a human dignity that shows through in his pho- tographs,” she noted.

I was curious what she thought about finding the book on the Schwemberger collection in an Irish cultural center.

“In Ireland you see the same kind of resilience. These people are also strong in their culture and their families,” she said.

Ireland suffered hundreds of years of colonization by foreign governments, most recently Britain. An armed rebellion in 1916 sparked the formation of the Republic of Ireland in 1949.

After thanking Ringlero and saying goodbye, I looked again at the Schwemberger photographs.

Mrs. Whitegoat was dressed in her best, except for her worn- out boots; something I hadn’t noticed until Ringlero pointed it out.

I’ll never look at a photo the same way again after happening upon the Schwemberger collection, or be surprised if a book shows up in what I might think is an unlikely place.

The University of New Mexico Press published “Big Eyes: The Southwestern Photographs of Simeon Schwemberger 1902 1908” in 1992.