Teaching the languages of the soul at home and abroad

BY COLLEEN KEANE

SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

TO’HAJIILEE, N.M./ NORTHERN IRELAND — During a time when there’s rising conflict around the world, there are also signs that some communities are joining hands and speaking with new, energized voices.

“The Navajo language has life in it. It fulfills your inner and outer self,” said Mary White hair, Diné, who teaches Diné language at To’hajiilee Community School.

“By using the Navajo language, students respond positively to it. It’s innate in them,” she added.

Thousands of miles away across the Atlantic Ocean, Geraldine McGloin from Ireland’s County Leitrim expressed similar sentiments about her traditional language.

“Irish (Gaelic) is the language of my soul. I’m re-awakening it, because it’s there. It’s in me,” she said.

McGloin was one of dozens who participated in a weekend Irish language workshop this past October. They travelled from all parts of Ireland to take the course at Oideas Gael, an Irish language school located in Gleann Cholm Cille on the west coast of the Emerald Isle.

Both here in the U.S. and in Ireland, colonizing governments invaded the people’s lands and in the process took aim at the fabric of their societies, their indigenous languages.

In the U.S., Native American students were forced by the federal government to attend boarding schools where they were often punished for speaking their tribal dialects.

“It was beaten out of us,” said White hair, who attended several boarding schools growing up.

Irish students experienced much of the same.

As an example, before Ireland won its independence from Britain in 1922, Irish-speaking youth attending British national schools were forced to wear tally sticks (bata scóir) around their necks. A notch was cut in the stick every time the child spoke Irish. By the end of the day, the child received a punishment for each notch.

This history has had a long-term impact.

As children grew up and lost their fluency in their native language, they couldn’t pass it on to their children or grandchildren.

Now, these children are feeling cheated. “It’s sad. You want to communicate with your grandparents,” expressed high school senior Tessa Jake, Diné, one of White hair’s students in her afterschool Navajo 101 class.

Kendra Apachito, Diné, feels the same way.

“I want to know about the elders’ stories and what life was like when they were growing up,” she said.

As she continues her studies, McGloin mentioned that she discovers traditional teachings embedded in the Irish language that are lost in English translations.

“It’s very difficult to translate the Irish language into English. It seems that there are no words to express the same sentiment; the essence, the fullness is not there,” she said.

For example, in English, the everyday greeting is a simple “Hello.”

But, in Irish one might say, “Féadfaidh an bóthar ardú suas chun beannú duit,” which translates into English, “May the road rise with you.”

“The person is actually wishing you good fortune,” explained McGloin.

White hair said it’s the same for the Diné language.

“The core Diné values are in the language,” she noted.

Pulling out a long list that she uses for her course, she pointed to one of the phrases – “Ha Hozho.” This expression is used by elders to teach children to be kind and generous to their relatives, friends, and neighbors, she said.

“This is very important to learn. We need to respect others,” said Apachito.

White hair said that To’hajiilee Community School is doing everything it can to give Diné youth back their language birthright.

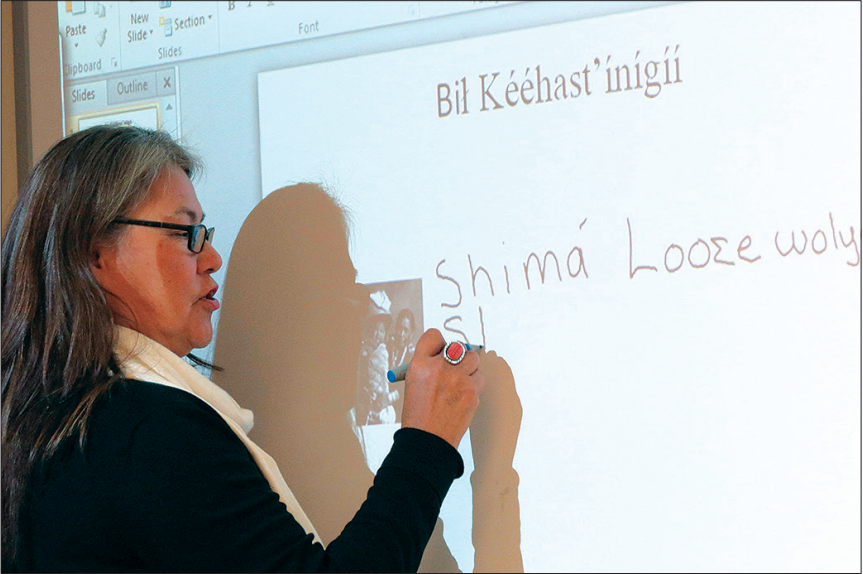

In her after-school classes, which are open to parents and community members, White hair uses a Smart Board to give an example of a story written in the Diné language as guidance for the final project. The class started last August.

Next to it, she color-coded words to show how they’re used in a sentence.

These are just some of many tools she uses to teach the Diné language.

“The Navajo language is very descriptive,” said White hair.

To help her students fi nd just the right words in the Diné language to tell stories about their families, she refers them to “An Introduction to the Navajo Language” by Evangeline Parsons Yazzie.

“I learned a lot in this class. I can now talk to my mom in Navajo. She’s proud of the way Ms. White hair is teaching us,” said Apachito.

To’hajiilee Community School is developing a Navajo language immersion curriculum that will be rolled out for Pre-K and Kindergarten students in the fall of 2017. The school will continue to add curriculum to other grade levels in upcoming years.

But White hair said that Diné language speaking needs to be reinforced at home and in the community.

McGloin feels the same about Irish. “We have to have opportunities to speak our language,” she said.

On Falls Road in Belfast, Northern Ireland, a historic church has been renovated into an Irish cultural center called the Culturlann McAdam O’Fiaich.

There, several people are drinking coffee and eating traditional foods in a cozy area set off as a café and speaking to each other in Irish. In an adjacent room, the artwork of Gerard Dillon, a well-known Irish painter is on display. In the bookstore, books by Irish authors and several books on learning the Irish language sit on shelves.

Kevin O’Shannon, one of the center’s managers, said that the Culturlann focuses on the arts to support Irish language revitalization.

“We have a drama society. We put on productions in Irish. We have Irish dancing classes and an Irish language choir,” he mentioned.

But he said what patrons like to do the most is drop by, have coffee in the café and practice speaking Irish.

“That’s what we need here,” said White hair, referring to the development of Diné-speaking coffee houses, sort of on-the-spot language nests that would give learners places to speak Diné in English-language dominated areas.

“If that awareness and visibility is there, maybe there will be more participation in speaking (our traditional language),” said White hair.

“We need to do this for our youth. We need to put Diné words back in their mouths so that it’s easier for them to start speaking it,” she said.

“I want to be able to visit the elders in our community and speak to them,” stressed Apachito.

From Aug. 28 to 30, the 2017 International Conference on Minority Languages called “Revaluing Minority Languages” is being held in Finland.

Information: www.jyu.fi .

ary Whitehair, Diné language instructor at To’hajiilee Community School, gives students an example of how to start a story about their families for

their final project.

Kendra Apachito, Diné, listens intently as Mary Whitehair, Diné language instructor at To’hajiilee Community School, gives instructions for a final project in her Navajo 101 afterschool class.